If I Could Hear Your Voice Again

W hen Rachel Benmayor was admitted to hospital, eight and a half months pregnant, in 1990, her blood pressure had been alarmingly high and her doctor had told her to stay in bed and get as much rest as possible earlier the infant came. But her claret pressure kept rising – this condition, known every bit pre-eclampsia, is not uncommon but can atomic number 82 to sometimes-fatal complications – and the doctors decided to induce the nativity. When her neck failed to dilate properly after 17 hours of labour, they decided instead to deliver the child past caesarean section under general anaesthetic. Rachel remembers being wheeled into the operating theatre. She remembers the mask, the gas. But then, equally the surgeon made the starting time incision, she woke up.

"I remember going on to the operating table," she told me. "I recall an injection in my arm, and I remember the gas going over, and Glenn, my partner, and Sue, my midwife, standing abreast me. And and then I blacked out. And and so the first matter I can remember is being conscious, basically, of hurting. And being conscious of a audio that was loud and and so echoed away. A rhythmical sound, nearly like a ticking, or a tapping. And hurting. I remember feeling a nearly incredible pressure on my belly, as though a truck was driving back and forth, back and forth beyond information technology."

A few months subsequently the performance, someone explained to Rachel that when you open up the abdominal cavity, the air rushing on to the unprotected internal organs gives rising to a feeling of great pressure. Merely in that moment, lying at that place in surgery, she still had no thought what was happening. She idea she had been in a car blow. "All I knew was that I could hear things … and that I could feel the most terrible hurting. I didn't know where I was. I didn't know I was having an operation. I was just witting of the hurting."

Every day, specialist doctors known equally anaesthetists (or, in the U.s.a., anesthesiologists) put hundreds of thousands of people into chemical comas to enable other doctors to enter and modify our insides. Then they bring us back again. But quite how this daily extinction happens and un-happens remains uncertain. Researchers know that a full general anaesthetic acts on the cardinal nervous organisation – reacting with the slick membranes of the nerve cells in the brain to suspend responses such every bit sight, bear on and awareness. But they nevertheless can't agree on simply what it is that happens in those areas of the encephalon, or which of the things that happen affair the most, or why they sometimes happen differently with different anaesthetics, or even on the manner – a sunset? an eclipse? – in which the human being encephalon segues from witting to not.

Nor, as information technology turns out, can anaesthetists accurately measure what it is they practise.

For as long every bit doctors accept been sending people under, they take been trying to fathom exactly how deep they accept sent them. In the early days, this meant relying on signals from the body; afterwards, on calculations based on the concentration in the blood of the various gases used. Contempo years have seen the evolution of brain monitors that translate the brain's electrical activity into a numeric scale – a de facto consciousness meter. For all that, doctors even so have no way of knowing for sure how securely an individual patient is anaesthetised – or even if that person is unconscious at all.

Anaesthetists have at their disposal a regularly irresolute array of mind-altering drugs – some inhalable, some injectable, some short-interim, some long, some narcotic, some hallucinogenic – which act in different and frequently uncertain ways on dissimilar parts of the brain. Some – such as ether, nitrous oxide (better known as laughing gas) and, more recently, ketamine – moonlight as party drugs. ("If you have an inclination to travel, take the ether – you go beyond the furthest star," wrote the American philosopher-poet Henry David Thoreau after inhaling the drug for the fitting of his fake teeth.) Different anaesthetists mix up different combinations. Each has a favourite recipe. There is no standard dose.

Today's anaesthetic cocktails have three master elements: "hypnotics" designed to render you unconscious and keep you that way; analgesics to control pain; and, in many cases, a muscle relaxant ("neuromuscular blockade") that prevents you from moving on the operating tabular array. Hypnotics such as ether, nitrous oxide and their modernistic pharmaceutical equivalents are powerful drugs – and non very discriminating. In blotting out consciousness, they can suppress not merely the senses, only also the cardiovascular organisation: heart rate, blood pressure – the body's engine. When y'all accept your old dog on its final journeying, your vet will utilise an overdose of hypnotics to put him down. Every time you lot accept a general anaesthetic, yous take a trip towards expiry and back. The more hypnotics your doctor puts in, the longer you have to recover, and the more likely information technology is that something volition go wrong. The less your doctor puts in, the more likely that you volition wake. It is a balancing act, and anaesthetists are very adept at it. But information technology doesn't change the fact that for as long equally anaesthetists have been putting them to slumber, patients have been waking during surgery.

A southward Rachel'southward caesarean proceeded, she became aware of voices, though not of what was being said. She realised that she was non breathing, and started trying to inhale. "I was just trying desperately to exhale, to breathe in. I realised that if I didn't exhale soon, I was going to die," she told me.

She didn't know there was a machine breathing for her. "In the end I realised that I couldn't breathe, and that I should just allow happen what was going to happen, so I stopped fighting it." By at present, however, she was in panic. "I couldn't cope with the pain. It seemed to be going on and on and on, and I didn't know what it was." Then she started hearing the voices over again. And this fourth dimension she could understand them. "I could hear them talking well-nigh things – about people, what they did on the weekend, and and then I could hear them saying, 'Oh await, here she is, here the baby is', and things like that, and I realised then that I was conscious during the operation. I tried to start letting them know at that point. I tried moving, and I realised that I was totally and completely paralysed."

The chances of this happening to you or me are remote – and, with advances in monitoring equipment, considerably more remote than 25 years ago. Figures vary (sometimes wildly, depending in office on how they are gathered) only big American and European studies using structured post-operative interviews have shown that one to 2 patients in one,000 report waking under anaesthesia. More, it seems, in Red china. More once again in Spain. Xx to forty thousand people are estimated to remember waking each year in the U.s. alone. Of these, only a modest proportion are likely to feel pain, let alone the sort of agonies described above. Only the bear upon can be devastating.

For Rachel, sleepless and terrified in her infirmary room, it was the beginning of years of nightmares, panic attacks and psychiatric therapy. Soon after she gave birth, her blood pressure level soared. "I was in a hell of a land," she told me.

For weeks later on she returned home, she would have panic attacks during which she felt she couldn't breathe. Although she says the hospital acknowledged the mistake and the superintendent apologised to her, beyond that she does not recall getting any help from the establishment – no explanation or counselling or offering of compensation. Information technology did not occur to her to ask.

Things can become wrong. Equipment can fail – a faulty monitor, a leaking tube. Sure operations – caesareans, eye and trauma surgery – require relatively light anaesthetics, and there the risk is increased as much equally tenfold. One report in the 1980s establish that close to one-half of those interviewed after trauma surgery remembered parts of the performance, although these days, with better drugs and monitoring, the effigy for high-take a chance surgery is generally estimated at closer to one in 100. Certain types of anaesthetics (those delivered into your bloodstream, rather than those you inhale) raise the take a chance if used alone. Sure types of people, too, are more likely to wake during surgery: women, fatty people, redheads; drug abusers, particularly if they don't mention their history. Children wake far more often than adults, but don't seem to be as concerned about it (or possibly are less probable to discuss information technology). Some people may simply have a genetic predisposition to awareness. Man error plays a part.

Just even without all this, amazement remains an inexact science. An corporeality that volition put one robust boyfriend out common cold will exit another still chatting to surgeons. More than a decade ago, I institute this quote in an introductory anaesthesia newspaper on a University of Sydney website: "There is no style that we can be sure that a given patient is asleep, peculiarly in one case they are paralysed and cannot move."

Last time I searched, the paper had been adjusted slightly to admit recent advances in brain monitoring, only the message remained the same: just because a person appears to be unconscious, it does not hateful they are.

"In a style," continued the original version of the paper, "the art of amazement is a sophisticated course of guesswork. Information technology really is fine art more than scientific discipline … Nosotros try to give the correct doses of the right drugs and hope the patient is unconscious."

The expiry rate from general anaesthesia has dropped in the past 30 years, from about one in 20,000 to ane or ii in 200,000; and the incidence of awareness from 1 or 2 cases per 100 to one or two per i,000. "Obviously we give anaesthetics and we've got very good command over information technology," a senior anaesthetist told me, "but in real philosophical and physiological terms, we don't know how anaesthesia works."

I t is possibly the most vivid and baffling gift of modern medicine: the disappearing human action that enables doctors and dentists to acquit out surgery and other procedures that would otherwise exist impossibly, frequently fatally, painful.

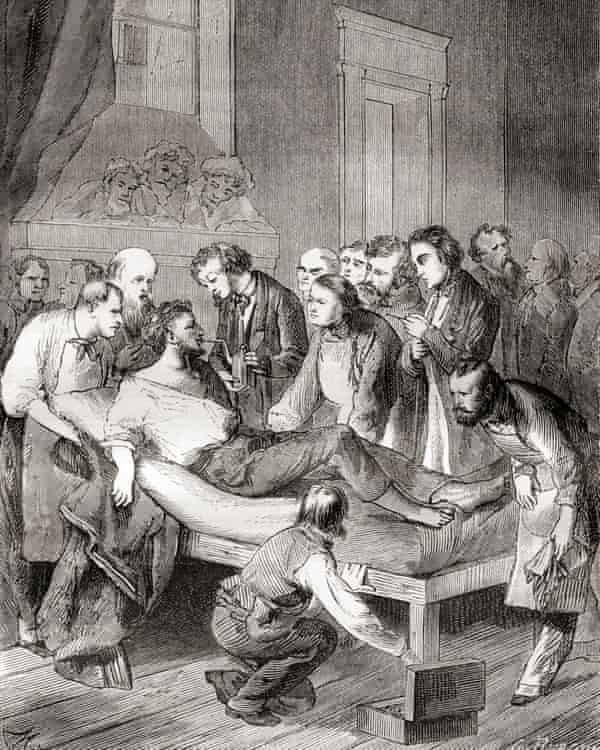

The term anaesthesia was appropriated from the Greek by New England doc and poet Oliver Wendell Holmes in 1846, to describe the effect of the drug ether following its get-go successful public demonstration in surgery. Anaesthetise: to render insensible. These days there are other sorts of anaesthetics that tin can numb a tooth or a torso, simply (or unsimply) by switching off the nerves in the relevant part of the body. Simply the virtually widespread and intriguing application of this skill is what is now known as general anaesthesia.

In general anaesthesia, it is not the nerve endings that are switched off, but your encephalon – or, at least, parts of it. These, it seems, include the connections that somehow enable the operation of our sense of cocky, or (loosely) consciousness, as well as the parts of the brain responsible for processing letters from the fretfulness telling us nosotros are in pain: the neurological equivalent of shooting the messenger. Which is, of course, a good thing.

I am one of the hundreds of millions of humans alive today who have undergone a general anaesthetic. Information technology is an experience now so common every bit to exist mundane. Amazement has get a remarkably prophylactic attempt: less an result than a short and unremarkable hiatus. The fact that this hiatus has been possible for fewer than two of the 2,000 or so centuries of man history; the fact that only since then have we been able to routinely undergo such violent actual assaults and survive; the fact that anaesthetics themselves are potent and sometimes unpredictable drugs – all this seems to have been largely forgotten. Amazement has freed surgeons to saw similar carpenters through the bony fortress of the ribs. It has made it possible for a doctor to hold in her hand a steadily beating middle. It is a powerful gift. Simply what exactly is it?

Function of the difficulty in talking about anaesthesia is that whatsoever discussion veers almost immediately on to the mystery of consciousness. And despite a renewed focus in contempo decades, scientists cannot yet even hold on the terms of that fence, allow solitary settle it.

Is consciousness one state or many? Can it be wholly explained in terms of specific encephalon regions and processes, or is it something more? Is it even a mystery? Or just an unsolved puzzle? And in either case, can whatever single explanation account for a spectrum of feel that includes both sentience (what information technology feels like to experience sound, sensation, colour) and self-awareness (what it feels like to be me – the subjective certainty of my own existence)? Anaesthetists signal out that you don't have to know how an engine works to drive a car. Only devious off the bitumen, and information technology is surprising how apace pharmacology and neurology give way to philosophy: if a scalpel cuts into an unconscious body, can it all the same cause hurting? So ethics: if, nether anaesthesia, y'all feel pain but forget information technology nigh in the moment, does it matter?

Greg Deacon, a former head of the Australian Society of Anaesthetists, told me about a patient who was waiting to have open up middle surgery. Deacon had been preparing to anaesthetise him, he said, when the human being went into cardiac arrest. The team managed to restart the recalcitrant heart, then raced the patient into surgery, where they operated immediately. It was simply in one case the operation had begun, the human's eye now beating steadily, that they could safely administer an anaesthetic. It all went well, said Deacon, and the homo made an excellent recovery. Some days later, the patient told doctors he remembered the early parts of the procedure before he was given the drugs.

"That is a sort of incidence of awareness which was thoroughly understandable and acceptable," Deacon told me: he had not even known if the man'south brain was yet working, allow alone whether he would survive an anaesthetic. "We were trying to go on him alive."

This is non denial. This is the tightrope that anaesthetists walk every day. They just tend non to talk most it.

I north 2004, and confronting a backdrop of growing public and media concern, America's Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations finally issued an alarm to more than 15,000 of the nation'due south hospitals and healthcare providers. The committee, which evaluates healthcare providers, best-selling that the experience of awareness in anaesthesia was under-recognised and under-treated, and called on all healthcare providers to outset educating staff about the problem.

The American Social club of Anesthesiologists subsequently acknowledged, in a 2006 practice advisory, that accidental intraoperative awareness, while rare, might be followed by "meaning psychological sequelae … and afflicted patients may remain severely disabled for extended periods of time".

Before that acknowledgment was published, however, and then ASA president Roger Litwiller made a small-scale but telling observation. Despite his organisation'southward business organisation well-nigh anaesthetic awareness, he did not want the event to exist blown out of proportion: "I would also similar to say that there is a potential for this subject of sensation to be sensationalised. We are concerned that patients become unduly frightened during what is already a very emotional time for them."

This is the anaesthetist'south dilemma. Under stress – which affects just virtually everybody facing a full general anaesthetic – we lose our ability and often desire to process complex data. More than half of all patients worry about hurting, paralysis and distress. High anxiety or resistance to the idea of anaesthesia may even contribute to anaesthetics declining, or at least increase the chances that nosotros will think parts of the operation. The more anxious we are, the more anaesthetic it may accept to put us to sleep.

This creates a quandary for doctors: how much to tell? When we are anxious, our bodies increase production of adrenaline-type substances called catecholamines. These can react badly with some anaesthetic agents. Then what does an anaesthetist tell a patient who, because of the type of operation, or their state of health, is at higher than boilerplate risk?

"I mean, nosotros're trying to make people not worry about information technology," said 1 Australian anaesthetist I spoke with, "but in the process I call up we blur it so much that people inappreciably e'er think nigh it, and that's probably not correct either … Should I be telling you that you've got a high risk of decease? Is that going to frighten you lot to decease?"

Today the profession makes much of the emergence of a new generation of anaesthetists who are more attuned to the experiences of their patients. But the reality is that anaesthetists remain for the large part the invisible men and women of surgery. Many patients nevertheless don't meet them until just before – or sometimes after – the operation, and many, deadened in a fug of drugs, might non even remember these meetings. Nor do anaesthetists generally leave anything to show for their piece of work: no scars or prognoses. When they practice get out evidence, it is invariably unwelcome – nausea, a raw throat, sometimes a tooth chipped as the animate tube is inserted, sometimes a memory of the surgery. It is unsurprising, then, that by the time an anaesthetist makes information technology into the popular media, he or she is generally accompanied by a lawyer.

For the doctors who each day brand possible the miraculous vanishing human action at the heart of modern surgery, this invisibility can be galling. It is non surgeons who have enabled the proliferation of surgical operations – numbering in the hundreds 170-odd years ago and the hundreds of millions today. It is anaesthetists. In hospital emergency rooms in Commonwealth of australia and other countries, it is not surgeons who decide which patient is almost in need of and generally probable to survive emergency surgery: anaesthetists increasingly oversee the pragmatic hierarchy of triage. And if y'all have an functioning, although it is your surgeon who manages the moist, intricate mechanics of the thing, it is your anaesthetist who keeps yous live.

O ne of the first articles I came across when I started researching this bailiwick was a 1998 newspaper by British psychologist Michael Wang entitled "Inadequate Anaesthesia equally a Cause of Psychopathology". Wang pointed out that pain – "even unexpectedly severe pain" – did not necessarily lead to trauma. Post-traumatic stress seldom followed childbirth, for example. What could be devastating, he said, was the totally unexpected experience of complete paralysis.

Even today, nearly patients undergoing major surgery have no idea that part of the anaesthetic mix will exist a modern pharmaceutical version of curare, a poison derived from a South American constitute, which causes paralysis. Few will be enlightened, either, that during surgery their eyes will be taped shut, that they may be tied downwardly, and that they will have a plastic tube manoeuvred into their reluctant airway, past the soft palate and the vocal cords, overriding the gag reflex, and into the windpipe.

For the patient paralysed upon the table, said Wang, "[t]he realisation of consciousness of which theatre staff are plain oblivious, forth with increasingly frenetic yet futile attempts to signal with diverse body parts, leads rapidly to the conclusion that something has gone seriously wrong. The patient might believe that the surgeon has accidentally severed the spinal cord, or that some unusual drug reaction has occurred, rendering her totally paralysed, not just during the surgery, simply for the residuum of her life."

Every bit presently as anaesthetists explain to patients how the process works, it all starts to seem a lot less mysterious. And talk, it turns out, is non just inexpensive but constructive: a preoperative visit from an anaesthetist has been shown to be amend than a tranquilliser at keeping patients calm. I know from my own experience – I had surgery on my spine – how reassuring such a chat can be. For me, it was non just the information; it was the fact of the human contact, of being treated as an equal, of beingness included, rather than feeling like an appendage to a process to which I was, after all, central.

Hank Bennett, an American psychologist, remembers a young girl whose mother brought her to meet him some time after the girl had her adenoids removed. The surgeon referred the mother to Bennett after she had returned to him in a state of anxiety near her kid. The surgery had been straightforward, but the mother felt that something was very incorrect with her previously happy daughter: the child had withdrawn from her family and friends, and had stopped working at school. She could no longer autumn asleep without her mother sitting with her, and was afraid of the night.

Bennett spoke with the girl. He told her there must be a reason she had changed her behaviour, and asked if it might have something to exercise with the performance.

Bennett recalled: "And she said, 'Yes. They said that they were going to put me to sleep, but the next affair I knew, I couldn't breathe.' Now, she was only momentarily similar that – she does not remember the breathing tube going in – but when I asked why she was doing these things differently at school and at home, she said: 'Well, I take to concentrate and I can't exist bothered by anything. I've got to make sure that I can exhale.'"

Bennett referred the girl to a child psychologist, and within weeks she was dorsum to herself. Today she would be approaching middle historic period. "But let's say that was simply luck," Bennett says at present. "What if cypher had been picked upward about that? Would she accept been permanently inverse? I think that you would say, yes, she probably would have been."

South o if you lot were my anaesthetist and I your patient, there are some other things I'd promise you would do in the operating theatre. Things that many already practice. Exist kind. Talk to me. Just a bit of information and reassurance. Use my name. Patients who remember waking are ofttimes greatly relieved at having been told what was happening to them, and reassured that this was OK and that they would now migrate dorsum to slumber.

The Fifth National Audit Project on accidental sensation during general anaesthesia states: "The patient's interpretation of what is happening at the time of the awareness seems central to its afterwards affect; explanation and reassurance during suspected accidental sensation during full general anaesthesia or at the time of study seems beneficial." Hospital staff could put a sign on the wall of the operating theatre: "The patient tin can hear". Because 1 of the strange things about anaesthetic drugs is that they can exert their effect in each direction – not just upon the patient, but upon the doctors and theatre staff performing the procedure.

After the teenage son of a good friend was badly burned in an blow some years ago, he had to endure weeks of intense pain, culminating each week in the agonising ritual of nurses changing the dressings on his chest and arms. They did this by giving him a dose of a sedative drug designed to distract him from the pain and foreclose him remembering it. My friend would attempt to comfort her son equally he yelled and as the nurses got on with their difficult job. What she observed was that while the drugs did give her son some distance from his hurting, and certainly his memories of information technology, they too gave the nurses some distance from her son. It was an understandable, perhaps necessary, altitude; but inherent in that tiny retreat (the lack of eye contact, the too-bright voices) was a loosening of the tiny filaments that connect us one to another, and through which nosotros know we are connected.

It is a process inevitably magnified in the operating theatre, where the patient is silent and notwithstanding, to all intents absent, and where their descent into unconsciousness is routinely accompanied past the sounds of the music beingness cranked up (one prominent Australian surgeon is said to favour heavy metal), and conversation. It demand not accept a scientific study to tell us that this deepening of respect and focus is skilful not only for patients, simply for doctors, too. In the end, it might non even much matter what you say. During an functioning, "a soothing phonation may be more of import than what the voice says," writes psychologist John Kihlstrom, who still encourages anaesthetists to talk to their anaesthetised patients ("nearly what is going on, giving reassurance, things similar that") merely acknowledges that he doesn't look them to understand any of it – not verbally at least.

Japanese anaesthetist Jiro Kurata calls this "care of the soul". In an unusual and rather lovely paper delivered at the 9th International Symposium on Memory and Sensation in Anaesthesia in 2015, he wondered if there might be "part of our existence that cannot ever be shut downwards, which nosotros cannot even conceive past ourselves" – a "hidden self" that might be resistant to even high doses of anaesthetics. He called this the difficult problem of anaesthesia awareness. I have no idea what his colleagues made of it. Only his conclusion seems unassailable.

"Any solution? Science? Yes and no. Monitoring? Yeah and no. Respect? Yeah. We must not simply be aware of the inherent limitation of scientific discipline and technology just, most chiefly, too of the inherent dignity of each personal 'self'."

Anaesthesia: The Souvenir of Oblivion and the Mystery of Consciousness past Kate Cole-Adams (Text Publishing Company, £12.99) is published on 22 Feb. To order a copy for £9.99, become to guardianbookshop.com

dabrowskiower1991.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/news/2018/feb/09/i-could-hear-things-and-i-could-feel-terrible-pain-when-anaesthesia-fails

0 Response to "If I Could Hear Your Voice Again"

Post a Comment